When I was 13 years old, I called round to the house of my school friend, Pete. Pete's family had recently moved into the Romiley area from Liverpool and, even though we were friends in school, this was the first time I'd called round to his house. Pete lived in an old townhouse. It seemed towering to me, and even had a name, Belmont. I loved it. There are some things I particularly remember about Belmont. It was three storeys high, with a dark basement below. I remember a beautiful grandfather clock on the left of the hall as you went in, and a framed, black and white piece of art on the right, portraying the seamless change, or polymorph, from bird to fish. There were sofas in two of the downstairs rooms - which seemed very grand to me - they looked soft, deep and inviting. The kitchen smelled of baking, usually bread or mini chocolate-chip cakes. And at the far end of the hall there was a door, which led down to the cellar, where I went on to spend some of the best, most exciting times of my younger years.

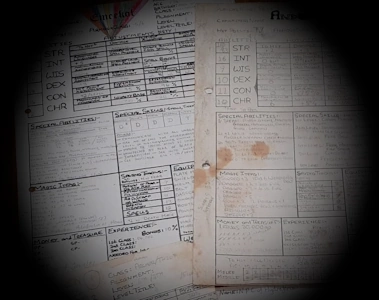

Pete's bedroom was packed with stuff. He had a bunk bed but the lower section was a desk. Amid all the books, papers, oddly shaped dice and coloured pens, was a map. An unfinished map, hand drawn on hex paper, which was stuck onto a block of wood. It was black and red, and I remember each hex was filled with a shape or symbol, such as a triangle or a tree, representing mountains and forests. There were made-up placenames as well, totally unfamiliar to me on that first visit, but even then they suggested lives being lived within.

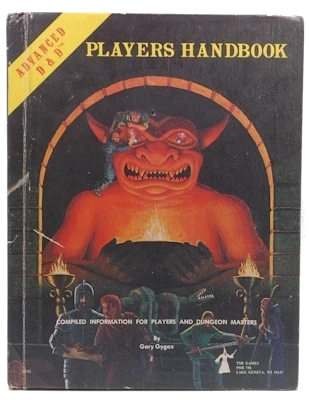

I asked Pete what the map was for, and I think that was when I first heard the phrase ‘Dungeons and Dragons’. Once he started to explain to me what it was, I had so many questions. I had always loved boardgames, but this game seemed so, so different. When I think back now, I picture myself as almost frozen by the sheer scale and endless possibilities that such a game could have.

In the years that followed, D&D in the cellar became a huge part of our lives. It was dark down there and always cold. We used a discarded piece of white, Formica kitchen top as our ‘battle-mat’, wax crayons for drawing the maps, and white spirit for wiping the top clean. I remember visiting Belmont around twenty years or so later, just before Pete's Mum and Dad moved south and before Pete emigrated to Canada, and the smell of wax crayon and white spirit was still there, along with the memories of those earliest adventures.

With a small group of friends, I started as a player within Pete's campaign. But before long, I had a go at being Dungeon Master. I had drawn the map of my world, along with other maps of villages and towns. I drew dozens of building and dungeon maps on graph paper pulled from the middle of school exercise books. My Mum and Dad had reference books all through the house and I used many of them as inspiration for names of everything. I filled in character sheets, one after another. And I could see it all in my mind, the gods, the landscape, the settlements, the heroes and the battles they would face.

I think I was an unconventional DM, more interested in the story than the rules. I loved it when a player surprised me with an idea, when a solution was found through ingenuity, when the highlight of a session was a war of words, when emotions bubbled to the surface and spilled into the real world.

The next ten years became filled with characters and their stories, some of which I remember more clearly now than many other things going on during that time. When the story continued with new players at university, the earlier years became the history upon which new, even greater adventures would be built. New players brought new characters. Seeds sewn as a boy grew into huge scenarios, which I tried to fuel and steer as best I could, the amazing players doing the rest.

One of those players was my great friend Mike. Mike recorded in detail all the adventures of his character, Balladir, so that in 2015, thirty-five years after I saw that red and black map in Pete’s bedroom, we agreed that writing a book of Balladir’s tale was something we both wanted to do. In fact, Balladir’s tale takes eight books to tell, and they are The Chronicles of Eynhallow.

Jonathan Roe